I have loved ones who aren’t white and they’re afraid that their children are going to get hurt. Because they’re not white.

I’ll repeat this sentence a little later on. It’s important. I hate fear and I bet you do too, and I bet that you’d do anything you could to keep children from being hurt. That’s what I’m really talking about.

I’m sorry if the title is offensive. It should be. I grew up in a place where signs like “White’s Only” and much worse hung everywhere; on water fountains, at the movie theater, at the Tasty Freeze.

Schools, churches, cotton fields; everything was separate.

Over the years I’ve trained myself to not use those words together in the same sentence… for whites only… unless I was trying to explain to someone about the town and the time in which I grew up and how segregation worked when I was a kid; how it misshaped me. But I’m using those words, that title, in a literal sense at this time. Folks who aren’t white do not need to read this. I’m not saying anything you’ve not heard before.

White parents fear for their children getting hurt, too. Parents of every color who care for their kids die a thousand deaths watching their children grow up; worrying about what might happen.

But in this country, a myriad of of factors have made it so that people of color have fears that white people don’t share. I’m sure we could spend a lot of time talking about white fears, but that’s a different conversation. I want to take a few moments to talk about why black lives matter to me.

Originally, I was writing this just for me. I wanted to think through my own evolution. How I grew from bigot to whatever I am now. So I journaled and then often I would share my thoughts with various friends who kept encouraging me to ‘put it out there’ so here I am, putting it out there.

I’m not qualified to talk on this subject to people of color. Folks who have endured things I’ve not endured don’t need to hear me as I get ‘woke’. I’m writing this for people who I can talk to because we share a privilege that most of us don’t understand. This is for people who are white like me.

The idea that whiteness can be a privilege is a controversial concept all by itself. But I’ve experienced it. When I was a child it was a way of life. The swimming pools you could go to, the places you could eat, the part of the movie theater you could sit in… the church you went to… I grew up in segregated America. I use the word privilege not to stir up an argument, but to nudge us towards a dictionary and search our hearts. A word that means ‘to have a special right, advantage or immunity as an individual or a group’ needs to be thoughtfully weighed out before launching an argument that continues to divide people. Things have changed a lot since the days of my youth, but the lingering reality of having enjoyed privileges that came from being white still haunt me.

I have shameful things to confess from my infancy. The way I remember my own childhood doesn’t reflect at all how I’d view another child. I believe children are innocent and impressionable and adults are the blame for the way a child grows up. But I’m sharing my memories at this time not to ‘beat up the kid in me’; I kinda love the child I was. But this innocent little kid had some really bad thoughts and was capable of saying and thinking really bad things. I have greatly repented and changed over the years. But examining the seeds of my bigotry and actions of my youth might help to make sure I’ve pulled the whole mess up by the roots.

I’ve always been told that I was ‘the good kid’. I made good grades, never had trouble with the law. Went to church. In fact I was the church kid who was the first to get baptized, first to go on a mission team. I never smoked, drank or cussed. Well, I didn’t think I cussed.

I remember a cuss word slipping out accidentally when my cocker spaniel with muddy paws jumped up on me one day. I was 6 years old and let the word ‘shit’ slip out of my young mouth. The truth is, I was yelling out loud at the excited, barking dog and was thinking “stop” and “shush” at the same time and my tongue got tied and I said a bad word. I was mortally afraid of hell at a very young age and I sincerely believed that cuss words were the shibboleth that open the gates to eternal damnation; and I believed that word which just jumped out of my mouth was one of the worst and now, even though I’d said it by accident, I still felt guilty instantly. And not just for that moment, but for years after, while a child, I’d remember that ‘sin’ and beg forgiveness in my nightly prayers; that’s how ashamed and appalled I was that I’d said a cuss word. On this I am not exaggerating. I never cussed as a child or as a young man and except for hells and damns still try to be careful about the language I use in public.

But… I grew up using the “n” word. Unless my mother heard me. She was the only one who’d ever correct me and it wasn’t until November 22, 1963 that I finally heard her. Sort of. I was 8 years old, Kennedy was shot, my third grade class cheered his death because he was a ‘n… lover’ and I merrily skipped home only to find my mother sobbing. They say that everyone who was alive that day can remember exactly where they were when they heard that Kennedy was shot. I certainly can and I’m still ashamed over 50 years later.

So, I didn’t cuss but I used the ‘n’ word frequently. I could add, ‘like everyone around me did’, except my mother, of course. But my mother’s influence became part of my conscience, and I went against my better inner voice frequently.

I have to own up to being a bigot in my infancy. I often followed the crowd as a child, and that crowd was really white. Fortunately, I was never in a crowd throwing rocks at little black kids trying to integrate a school, but when I see the archival footage about Central High School in Little Rock, my state’s capital at the time, I get chills. I could easily have been one of the little white kids shouting “Go home n___!” If I had been standing with my class mates and they were shouting, I’d have been shouting too, I fear.

As a 61 year old man, even though I’ve changed so much over the years, I feel no consolation that the stupid thoughts I had as a kid were not mine but just the product of “the times I grew up in”. These things misshaped a part of my brain. I believe they’ve long been exorcised, but I never want to mis-remember how bad it was. I never want to relive those thoughts or times, but neither do I wish to rewrite them. I see no good coming from acting as if it never happened or pretending I was something that I wasn’t.

That’s why my adult conversion to Jesus is so precious to me. By the time I became what I consider “a true believer” I had already changed from the blatant, ‘n’ word saying little bigot to a slightly more aware young man; but my conscience was scarred not just by the things I said and did but by the things I can imagine I could have done had I been at the wrong place at the wrong time. I remember so many racist anecdotes from my young life that still convict and shame me.

When I was 7 years old we rented a house in Des Arc, Arkansas. That was the nicest house I’d ever been in up to that point in my life and the icing on the cake was a big pecan tree right in our front yard. I went out the door one day and saw a couple of children of color climbing in the tree shaking out pecans while another child picked them up. I yelled the ‘n’ word at them as ferociously as any tiny cracker ever yelled it.

“You n___s get out of my pecan tree!”

No sooner had those words left my lips than a firm hand grabbed the nape of my neck and pulled me back into the house and I got a tongue lashing about how awful it was to use that word. I wasn’t scolded for fussing over a brown paper sack half full of pecans. I was being reprimanded about using that word just as if it was a cuss word.

But it wasn’t my mother who had jerked me back into the house. It was ‘our maid’.

I bet my dad made slightly more money than it took to put food on the table, but he still had enough to hire Sandra to do our washing and ironing and light cleaning and the occasional baby sitting, which included yanking me in the house that day when she heard me go off on those pecan thieves. Sandra was a young woman of color and she can be credited with giving me my first taste of humble pie.

First off, the kids were her cousins, and she’d asked my mom if it was okay for them to have a bag of pecans. Secondly, if they’d been strangers, if I’d not used the ‘n’ word; if I’d not noticed they were starving compared to me… the decent thing to do would be to share pecans and make friends. I’m still embarrassed about that moment 54 years ago when my true colors came out and they were slime colored racist.

I went back outside and apologized to the kids and helped them fill the bag of pecans before they went on their way. I wish I could say that from that day on I never used that word again, but I’d be lying. Years would pass and I’d start shaving and driving before I learned there was no circumstance under which it was or ever would be okay for me to use that word. It’s humiliating to even write the word in censored form in this essay. I can’t blame the times, culture or lack of opportunity for the incredibly slow process involved in learning how bad my heart was. I was a child and I thought like a child but I can still remember having the choice to be kind or to be cruel and I have no excuse and have to admit I often chose poorly in my youth.

So, yeah, the “N” word was common when I was young but I’ll tell you a word unheard of in those days, and that’s the word ‘racist’. I didn’t know what racism was. I knew what it meant to be different and to fear what you don’t know, but I didn’t realize what I was programing myself to think, or why. And no one I knew, none of my teachers in elementary school, ever added the word racism to my vocabulary.

And they could have. The word was added to the English language in 1902 by a man named Pratt who was actually a racist famous for saying, “Kill the indian, save the man!” https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2014/01/05/260006815/the-ugly-fascinating-history-of-the-word-racism

Only my mother and Sandra ever gave me cause to consider the ‘n’ word as anything but appropriately descriptive. Not my culture, not my school; not even my church. The churches I went to actually nurtured this view. In fact, I would come to believe that it was ‘uncool’ to be a racist before I would understand that it was a ‘sin’.

So, when did I change and what changed me? My wife assures me that by the time I was 20, when she met me, that I showed no signs of bigotry. Like I said, it wouldn’t have been ‘cool’.

I think that by the time I was 14 I began to change significantly. I lived in Granite City, Illinois, which had been a sundown town up until about the time we moved there in 1967. A town with a 40,000 all white population within sight of the Arch in St. Louis, I only knew civil rights issues from watching the news and listening to the radio. A youth minister who was white, had long hair and Elvis sideburns and was just coming back from India made a huge impact on everything I believed and I still thank God for Terry Bell and his love of Jesus and young people and the difference it made with me. Those were my late 60s and while the world was getting ‘turned on and tuning out’ I was in the middle of adolescence and imagining the world the way Jesus would have it.

In 1970, just before my 15th birthday, I read “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee”. The book was my first introduction to genocide and told me a story of which I’d been completely ignorant.

Up until that time I’d been a boy scout and I think I was just about as patriotic as any little white American boy could be. But these were the Viet Nam years, and between the protests I saw on T.V. and the genocide I was reading about in Dee Brown’s book, my ideas about patriotism and waving the flag changed forever.

At 19 I went to live in Trinidad with a preacher named Bob Brown. He was missionary and a wild man and became one of my early role models and mentors.

Bob Brown in a cotton tree in Dominica.

Bob had grown up in Pascagoulah, Mississippi. One of the most profound influences in my life was a book he gave me by Pulitzer Prize winning author, Ira Harkey, called “The Smell of Burning Crosses”.

In those days it was common practice in newspapers to address white people as Mr. or Mrs. or Miss, but the same courtesy was not extended to people of color. Ira Harkey got rid of those titles altogether and would not identify a person’s color unless it was a necessary part of somethings like a fugitive’s description. He did away with “The Colored Section” of the newspaper and mixed the white people’s news with everyone else’s and as a result was shot at and the KKK burned a cross in his front yard.

I vividly remember the impact of this book. Immediately, I adopted Harkey’s way of seeing and talking about people. For example, let’s say there are three men in a group: Mo and Larry are white; Curly is black. These are my buddies. You ask me, “Which one of those men is Mo?” I’d use his shirt color, or height, length of hair… anything except skin color… to identify him. But if you asked me which one was Curly, I’d have immediately said, “The black dude.” After reading Harkey’s book, I stopped doing that altogether. I’d use color of clothing, height… anything except skin color.. to describe someone. I became “color blind”. I know, I know. We’ll talk about that in a little while.

THEY ALL LOOK ALIKE. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/20/nyregion/the-science-behind-they-all-look-alike-to-me.html?_r=0

Up until this time when I saw a crowd of non-white people I’d only see color. This was 1975 and the phenomenon of people of one race not being able to distinguish another hadn’t been researched, at least not as much as it has in recent times. It’s a weird, kinda sad thing, but I could recognize Muhammed Ali or Bruce Lee; but if I looked at a crowd full of black people or a room full of Asian people, it was just a sea of “they all look alike”. This didn’t happen with white crowds. My brain could dissect a room in mili seconds, especially singling out the prettiest girl. This changed for me dramatically in Trinidad.

I remember after a few weeks of living in Port of Spain and reading “The Smell of Burning Crosses” I saw a young man who looked exactly like my cousin David. They had the same figure, features, mannerisms. But something was different and it actually took me a few moments before I realized the only difference in their appearance was skin tone: I was looking at a black man thinking he looked looked almost exactly like my white cousin.

Living in Trinidad and reading this book changed the way I would ‘see’ people. I’d grown up in Arkansas and moved to Illinois when I was 11. I went to school in Tennessee. For most of my first 19 years that was the extent of the world I’d seen. I’d been to Florida once, when I was 17, and saw the ocean for the first time. So now, at 19 and living in the Caribbean on an island that was only 3% white, I was ‘a minority’, influenced by a white man teaching me to be ‘color blind’ and seeing people’s physical features to the point that I completely lost the “they all look alike” filter.

I dove into West Indian culture. I loved the people, the food, the music… remember, it was 1975 and I’d never heard of Rastafarianism… everything was ‘dread’… Bob Marley was still singing and when I found out Eric Clapton didn’t write ‘I Shot the Sheriff’ my world got a lot bigger.

This is me baptizing a lady and her son in the bay near Scarborough, Tobago.

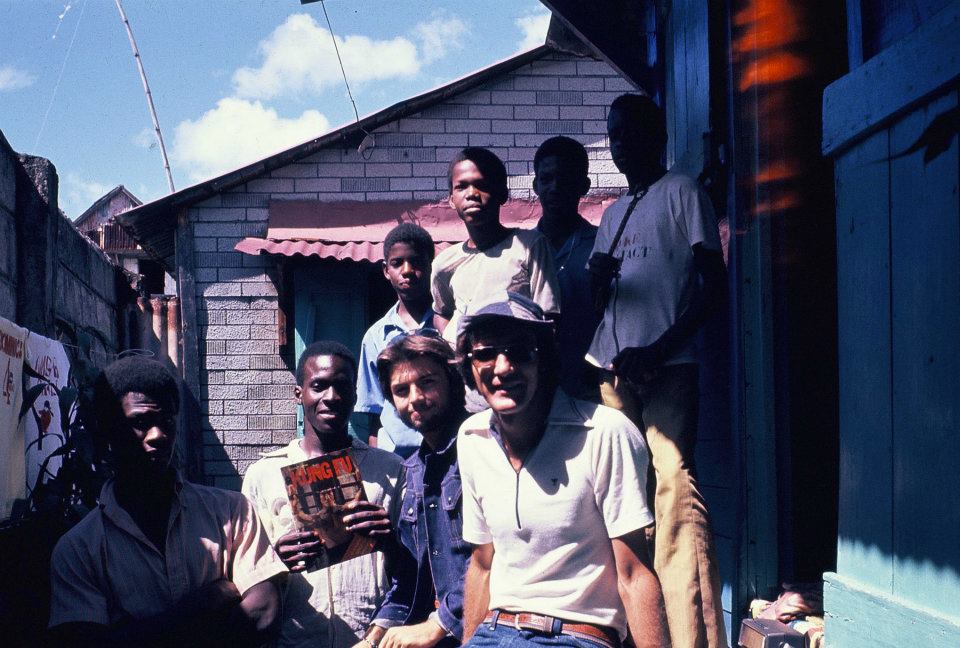

This is me with some friends in Dominica. The guy in front to my left is Melvin Duke. I was 19, he was my 35 year old room mate for three months. He’d taken three months off to visit the Caribbean and do mission work. We traveled and worked together for a while, but he went back home and I stayed for almost 8 months.

Over the next two years I’d go back home, meet the love of my life and get married; and when it comes to race I’d totally believe everybody should be color blind. My vision of a Christ-like world was filled with people who loved and lived together totally ignoring color. I’m aware I was not alone and this can easily get mixed up with Dr. King’s warning against ‘moderate whites’ which would become ‘white neoliberal’. I make no claims to understand all the pros and cons of these ideas and respectfully defer to people of color in regards to trying to learn how to think and talk about race relations. I can just tell you that the impact of Jesus founding a church of ‘neither male nor female, slave or free, Jew or gentile’ gave me the greatest vision I’ve ever had of what the world is ‘supposed’ to look like. By the time Lisa and I started a church in Manhattan in 1983 I wanted to be part of a church where color did not determine leadership or membership, and in time set in motion my goal to be replaced by a man of color. But it would take years for me to understand that while I was trying to talk everybody into seeing the world the way I wanted it to be, the way I thought Jesus wants it to be… I’ve been envisioning from a perch of privilege while most of my non-white brethren still suffer indignities and fears that I still can’t quite comprehend.

A disclaimer here: I’m writing to my white friends in my church fellowship. This fellowship is one of which I’m happy and proud to belong. We’re identified as the International churches of Christ. We’re surely not without our problems, but I’m very thankful that from the beginning we’ve always intended to be a multi-cultural, diverse fellowship. However, most of us probably do not understand the role our bible-belt roots have had on the relationships between people of different colors in our fellowship. The past haunts all of us whether we know it or not.

If you study the history of the churches of Christ, you’ll see the birth of a system of faith so fresh in the shadow of “The Great Awakening” that it would soon be identified as a prominent part of what is called “The Second Awakening”. It was a white man’s religion and called The Restoration Movement. I don’t think the fact that it started with white men necessarily makes it corrupt. The first church during the first century began in the shadow of the cross and was at first a Jewish movement. But the difference is that 2000 years ago, in obedience to the Lord’s command to preach to “every creature in every nation”, that fellowship quickly became very diverse. The first century church was born in an exclusive culture, but with a mandate to change and change it did. The first church soon became inclusive regardless of race, nationality, social standing or gender.

1700 years later the Restoration Movement would be different in this regard. The gospel spread to people of all colors in this country, but did so separated along the same lines as both law and culture might dictate.

The International churches of Christ grew out of this Restoration Movement. The principals which began this line of religious thought were born in the petri dish of genocide, manifest destiny and adventurism. Those churches, and the men and women who preached in them, are fascinating and have stories that contain so much forgotten information that if you made a hobby of researching them you’d realize that you know as little about all the diverse events and warring ideas that shaped our movement of churches as you might have about your own great, great grandparents or other distant relatives. We have a rich heritage of independent thinking and heroic discipleship dedicated to truth. But we also have shameful skeletons buried in the closets of church history that I’d just as soon forget if it wasn’t for that the fact that those skeletons still affect us to this day. Some of the women and men should still be considered brave and noble for their willingness to fight against injustice; but that doesn’t negate the thousands of cautionary tales about bigotry and distorted theology that may still be deforming us unnecessarily.

Most of us are unaware of the role the churches of Christ played in abolition or the women’s vote; some churches were lead by men and women who were anti-slavery and later anti-misogyny; but cataclysmic divisions over both those issues divided congregations in the 1800s. Slave owning factions of Restoration Movement leaders planted the seeds of privilege which produced bigotry and segregation in virtually all of the Churches of Christ and Christian Churches until after the 1960s and the civil rights movement. In fact, I’m afraid churches of Christ, like Christian churches and so many other groups, need to admit that societal changes actually sparked church changes in our brotherhood rather than the other way around. I’m a preacher, and a disciple, and I am biased; I want to think that every great moral, social advance had at its core someone who preached Christ and stood opposed to social injustice. But I’m afraid the facts might not bear that out. I believe had there been no Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement the multi-racial congregations we see today probably would not exist. And while I respect that Dr. King was a preacher and God centered man, the Civil Rights Movement was ecumenical in nature and involved Christians, Muslims, Jewish people and Atheists. I believe the core tenets of that movement are Christ-like, but I can’t appropriate the impact of men like Dr. King into my history or theology. Modern day Christians of my persuasion have often been the last to stand up against social injustice. We’ve had our reasons and we’ve had a few exceptions. Calvin Conn was one of my friends and mentors and he led an integrated campus ministry at Ole Miss which fought against racism in the 60s. Not long after that he spearheaded the first, and at the time only, integrated church of Christ in Chattanooga, Tennessee. However, he stands out as an exception. Our custom in the ICOC has been to focus on bringing folks into the church and let the world continue on it’s way to hell. It’s still difficult for me to think differently than that myself, but the number of people of color inside our fellowship who are experiencing unacceptable levels of fear and unfair treatment might call for us to reconsider how involved we ought to be in fighting social injustice in this country. I’m sure we’ll disagree on that as much as churches disagreed 150 years ago on emancipation and later on the women’s vote.

( here’s an example of what you can find if you’d like to dig just a little https://books.google.com/books?id=-3UtqrX56rgC&pg=PA3&lpg=PA3&dq=abolition+john+boggs&source=bl&ots=HiWOnt6Ezl&sig=hj6s4nBlkIMWxUG9_wVIAqh01po&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwirgIq686PRAhUpwVQKHaq_DUMQ6AEIGjAA#v=onepage&q=abolition%20john%20boggs&f=false )

And that’s how, in spite of the fact that some of the restoration movement’s heroes took part in the underground railroad, I could still grow up 100 years later in a segregated church of Christ where saying the ‘n’ word from the pulpit was common and worshipping with black churches on special occasions was still a radical thing for white people to do. Our intention is to be a church that disregards centuries of man made religion and adhere to the same call the first disciples advanced throughout their world. We want to date our origins back to the first century church and skip past all of the mistakes and atrocities of multitudes of groups who called themselves Christian while murdering and slaving with theological immunity. But to do that we need to first undo some thinking which lingers from even more recent times.

Like I said, months ago I started writing to myself about why black lives matter. I’m very late in speaking up for my friends and speaking out against some things that I believe are ungodly. If you’re neither part of my fellowship nor a religious person at all, I hope you’ve figured out by now that I’m a preacher. I use bible words like ‘ungodly’ and ‘sin’; and sound like I’m talking in church. I am. I began writing this because I love the fellowship to which I belong and think we can do better.

I think we’re a good intentioned bunch of people. We disagree on many things and still love and get along with each other. For some of us we’ve spent most of our adult lives together. Please forgive me if I’m trying to tell you something you already know. If you got there ahead of me, good. But things I’ve seen and heard recently, as well as having received numerous sad stories from brothers and sisters who are not white, compel me to say that we fellowship in a body that does not equally share fear and frustration.

I know many who are white also live in fear and frustration. Words like “privilege” and phrases like “black lives matter” make their defenses go up. They don’t feel privileged. That’s one reason why when you say “black lives matter” some white folks are going to retort “all lives matter.” Especially for the white people living below the poverty line. For them to agree with a world view that puts them on top of anybody is hard to fathom. The historical truths of systemic racism and genocide are vague and ethereal compared to their own hard times and mere survival. Desperation doesn’t always bring out the best in people.

I realize a lot of white people who aren’t poor also retort “all lives matter”. If I were to pick a fight, they’re the ones I’d go after. It’s one thing for someone to not empathize with people of color because they’re own lives are so miserable they can’t bring themselves to find time or energy to empathize. But for most white people, responding to “black lives matter” with the retort “all lives matter” shouts racism and here’s why.

Some white people think that emancipation, civil rights, and affirmative action prove that race relations among people in this country have improved so much that the discussion is unnecessary. If you’re comparing ante-bellum slavery to having a non-white president, I’d have to agree. Many things have changed. But it’s not as simple as that.

Some of us are still promoting that ‘color blind’ approach to church life that I was talking about. One of the problems with being color blind is that it doesn’t acknowledge the atrocities still going on all around us. As I said, I spent my young adulthood spouting the same philosophy; thinking a color blind church was a more Christ-like church. Thinking the interracial marriages and diverse makeup of our congregations spoke loudly for us: we are better than the rest. But the events of the last few years have made me re-examine my life, my view point, and my history. Only my determination to be in a church without racial borders presses me to take this further than I’ve ever known I could go. The emotional disconnect between people who are supposed to be family alarms me and I think we can do better and I think we want to do better.

“Black lives matter” is a statement of fact that I support. I’m aware that there is an organization with the name Black Lives Matter. I can’t claim to know much about that. I’ve researched and followed that group and appreciate anyone who raises awareness and begins a discussion with the kind of far reaching impact that “Black Lives Matter” has made. But I don’t know that I could share agendas with a group as amalgamated as I perceive they might be.

But for me to make the statement “black lives matter” is easy; a no-brainer. Rolls off my tongue just the same as saying “I love you”. It’s personal; faces of people I care for are involved; families and friends and children. Their lives matter. The words ‘black lives matter’ is simply a statement of fact.

To say black lives matter is to acknowledge that racism is still a reality for people I love and just plain wrong. And to say black lives matter is my effort to carry on a conversation about why racism is something only white people can perpetrate. There’s plenty of other sins like hate and malice… well all of the sins… that know no racial boundary; you’re a sinner no matter what color you are. But racism, at least where we live, is a white sin. That’s maybe the hardest thing for white people to accept. Let’s not stuff this one. Let’s talk about it. If you’re white and you disagree then please ask your friends of color what they think and why and just listen. James said be quick to listen, slow to speak. I’ll take a huge liberty and say, on this one point, be quick to listen and stay silent no matter what. We can afford to stay silent and absorb this one. We should be willing to do that for at least a few hundred years.

Saying “black lives matter” is assumptive: I assume it’s already established by centuries of history that white lives matter… a lot. Historically, in this country and other parts of the world; white lives have mattered more than black lives, and laws have supported that view. Saying Lincoln ended slavery or that the civil rights movement ended Jim Crow is to miss the bigger picture and put ignorance on display.

Not that long ago even church history records that a whole culture of people claiming to be Christian believed that white lives mattered more to God than did black lives. Many churches had a distorted theology lifted from scripture to support that view. This is a fact and has given some people a reason to have no interest at all in “christianty” … small letter ‘c’… which can be argued is nothing more than a man made white religion. True “Christianity” … capital letter “C” is supposed to be different.

So for me to say that black lives matter is to affirm that I believe all souls are equal; but that a whole lot of people are still treated with disrespect, fear, and discrimination because of skin color. To say black lives matter is to affirm two things that I believe: 1). All non-white lives matter, and 2). not all white people agree or understand.

To say that black lives matter is to understand that in spite of emancipation, in spite of the civil rights movement, in spite of desegregation, in spite of affirmative action, in spite of having black heroes in sports and film and politics… EVEN in spite of having a black president… so many white people won’t acknowledge that black lives do not matter to white people as much as do white lives.

We white people are more eager to cite the changes and progress that we ‘know’ have been made. Affirmative action is big for many of us. The litany of facts that might affect real change of mind are too easily dismissed by distortions of truth and thoughts like “I never owned any slaves” or “slavery was a long time ago” or “get the chip off your shoulder”. The impact of the 13th Amendment is lost in a debate in which white people need to be right more than we desire to understand.

Black lives matter. This shouldn’t be a problem for any preacher to say in his church. A church of diversity should already be on the road to understanding we are all the same. But, in my congregation, we DO NOT all have to take the same precautions, deal with the same fears, endure the same discrimination or have the same kind of precautionary talks with our children. So sometimes, if I make the statement “we are all the same” then I’m either being ignorant, insensitive, or deliberately attempting to protect the status quo of a fallen world that loves to exalt one person over another. Because, though I believe we are all the same in God’s eyes, we do not all suffer the same. Saying we’re all the same sounds like I’m ignoring the fact that many of my dearest friends are not allowed to share some of the things I take for granted.

Of course I believe that everybody matters. That’s exactly why I believe I must say black lives matter because too many white people still demote the importance of my loved ones who are not white. Some do so out of ignorance, some intentionally. Either way it needs to change.

I’ve heard many non-white people say “all lives matter” followed with an immediate “of course they do!” But if a white person says “all lives matter” it can be interpreted as a defense of the status quo, a status quo that sometimes puts my loved ones in more fear then I’ve ever had. So, I avoid the phrase “all lives matter” because it has become a white retort and a movement unto itself.

But if a non-white person were to say “all lives matter” I’d view them as a person who takes a Godly view of the world and is proposing the way everything should be. Does that sound unfair? That because of color one person can say something that you can’t say? You’ve got to get this. It’s that important. Yes, because of color, some people can say things you can’t say.

I’m noticing people of color are more likely to say ‘every life matters’. I think that’s to make a distinction between a racist retort and a desired reality. And when I say black lives matter it’s a statement I make in a world where white lives already mattered and have mattered for a long time.

Why say this now? I have plenty of friends who could ridicule me for taking so long to be ‘woke’. I have plenty others who know me better. What I’m writing has come out of hundreds of discussions I’ve been having for years with friends of all colors. And what I’ve heard repeatedly is that I need a white audience to hear me say these things. I’m not at all sure it will help or do any good at all. But I do have hope and here’s why: I have many, many white friends… in and out of church… who, when I tell them some anecdote about a black friend of mine being called the ‘n’ word, or worse, they’re response is “NO! Really?” They’re honestly surprised. Amazed. Aghast. Unaware.

Some of us are living in a white bubble in spite of being in constant contact with people who are not white. Nice contact. Friendly contact. Warm and kind contact.

When a small community like mine still has white people who are still oblivious to what it still means to be ‘driving while black’ or stalked by security while shopping or to have racial slurs yelled out of passing cars and sometimes even closer face to face encounters; then I guess there might be a need for us white brethren to talk to each other about this.

And here’s a painful truth: in our fellowship many members of color have given up on white brothers and sisters ever understanding. In spite of multi-racial leadership in many of our churches, and in some cases, because of multi-racial leadership in our churches… our brethren who could enlighten the white folks have learned to keep it at home or just amongst the black folks. The tendency of our leadership is to play down these issues. But this often leaves our non-white members gagged and the white members blissfully unawares. Oh, we’re aware there’s a problem “out there”, in the world, but in the church all seems well. And to an extent it is and who wants to stir up church drama? But this impasse leaves many of our black brethren bearing their cross alone, just amongst themselves; which keeps our community emotionally divided and does nothing to help us truly become a family sharing each other’s burdens.

Understanding that black lives matter is vital to a real agape fellowship of believers. This is part of defining what kind of church I can be in. This defines what kinds of friends I can have. Saying black lives matter for me means I’ve spent most of my life thinking that I was ahead of the curve while in reality I was probably one of the moderate whites Dr. King warned about, and I never even knew what he was talking about. I’ve always thought that I loved and respected everybody. But it’s embarrassingly late to now realize that I was smiling from the box seats while many of my loved ones were bleeding in the arena.

In slave days you’d have had no problem getting plantation owners to say, “black lives matter.” Black lives mattered and could be equated in dollars and cents. In this country an equation of some sort has always existed to calculate the value of a black life, whether economically, politically or competitively. So today when someone says “black lives matter” it’s an attempt to change the equation. It’s a human and humane attempt to balance the scales and make us all truly equal. This is something in my experience and faith that only Jesus can really do, but I see an awful lot of Muslims, and Jewish people, and all kinds of folks different from my faith and some with no religion at all already practicing it. I’m just trying to hang on to Jesus, love my neighbor and catch up with so many of the rest of the world who are already doing this.

But that brings me to where I started. I have loved ones who aren’t white and I know for a fact that they are afraid that their children are going to get hurt. Because they’re not white.

They hear it when people say “well, just teach them to be respectful and how to act; teach them how to act with police and if they’re not doing anything wrong they shouldn’t be in any danger.”

You think that’s not what a black mother or father isn’t already teaching their children? You think there’s not already “that talk” where people of color have to tell their children where to put their hands, where to put their voice, where to put their eyes…” You think that talk isn’t going on… hasn’t been going on for years?

So, for all of you who are ‘white like me’. White. Where did that come from? I’ve met very few white people in this country who didn’t claim to have some “native American” blood. That’s become more fashionable with my generation for some reason. But many of us so called ‘white’ people had white raped into our DNA and don’t really know where we came from. For those who claim to hail from a strictly white lineage I wish you the best. If we go back far enough we seem to have some common ancestors and the argument that skin color has been politicized becomes undeniable.

As a preacher, I live in a fairly insular world mostly surrounded by love and understanding. Even when we disagree most of my church family and friends have learned how to respect each other and have calm discussions. But sometimes we only let out our Christianity go so far. Jesus started a church with precepts for membership being ‘neither male nor female, Jew or gentile, slave or free.’ What would He say today? Do we even need to ask that question? Has he not spoken for the ages? Doesn’t his life and message destroy any semblance of racism?

My wife asked non-white members of our congregation if they’d like to share incidences of racist treatment they’d received. I’ll just share the tearful testimony one of our sisters, a wife and mother, and dear friend of my family:

“While at work a woman confronted me and explained, “Why do black people hate the word n*****? If you’re not a n*****, then it shouldn’t bother you.”

An elderly resident in a senior community where I worked said, “You would think that you would be better at serving people. You know… with your people and all.”

Another resident could not find her belt. She told my manager , in front of me, “She took it. They can’t help it they just take things sometimes.”

Someone I thought was a friend said, “I feel like every black person I meet has a chip on their shoulder. Slavery was a long time ago.”

While I was pregnant I could not wear my wedding band because my fingers were so swollen. Once while riding the bus to work another passenger told me that ” if my people cared more about marriage I would not have to work so hard”

Once while shopping I had to ask an associate where the black hair products were. After she showed me and I was telling her that I was getting something for my daughter’s hair. She looked at Jaeden’s and said “if I had a girl with hair like that I would just shave it off”

While in the grocery store a woman commented that my kids were really cute but that all of my children look so different from each other. And then she asked me if any of them had the same father?

While at the park in Northwest Portland I was chatting up Mom’s because my young son was having a hard time playing with his peers. While talking to the other moms I was informed that this is more of a “neighborhood” park and that it would be better if I took my son to a park in his own neighborhood. I lived across the street.”

But we didn’t stop there. We asked people of color who are part of our fellowship what kinds of insensitive things had happened to them within the churches. A few of my closest friends were willing to talk to me about it; no one, so far, has been willing to write about it. Stories of ignorant insensitivity and joking about the ‘n’ word haven’t been uncommon but more blatant discrimination is difficult to talk about because the desire for unity and getting along is great, as is a feeling that white people don’t really want to listen. This was a common theme I’ve heard; that many disciples of color would rather not try to talk about this anymore and are hoping that some white leaders will say something to white people. I think if white disciples would be willing to really listen more of our non-white family might be more willing to have some long, tough talks that could make us all better and might just possibly destroy the wall that keeps so many of us from being emotionally connected.

Seems to me that Christians should understand that this is a fallen world and it’s going to have bigotry and hatred and evil running amok from now until Jesus comes back. That doesn’t mean that we don’t resist. That doesn’t mean that we have to capitulate to the evil. We can support our brothers and sisters of color when they protest for change outside the church. I’ve come to believe we should join them and lend our voices to shout for change outside the church. But the only place we can demand and expect that people be treated equal is IN the church and right now I believe that we need to understand that we don’t all live in equal fear. Some of our family are suffering and sometimes, what they must endure is worse than mere fear. And doesn’t the bible teach that when one part suffers we all should feel the pain? We need to listen to our brothers who are suffering and be sure they know… that we all know… that their lives matter.